[Design Patterns] The Decorator Pattern

Previous Posts:

[Design Patterns] Why do we need them? / The Strategy Pattern

[Design Patterns] The Observer Pattern

Learning the Decorator Pattern

In this post, we are going to learn the Decorator Pattern.

With this pattern, we can learn how to decorate our classes at runtime using a form of object composition.

We can also give our objects new responsibilities without making any code changes to the underlying classes.

The Starbuzz Coffee

We are going to learn this pattern by designing a system for a coffee shop.

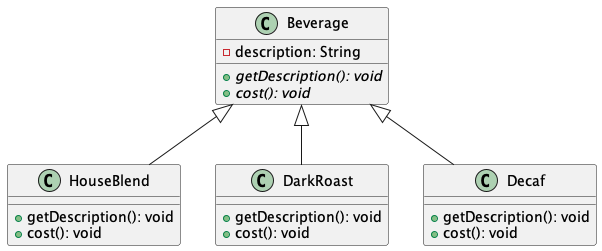

When the coffee shop came to the business, they had the following class design for their beverages.

However, there is a problem with this design.

What if the customers want a variety of options? What if the customers want a HouseBlendWithSteamedMilk andMocha?

If we create all the instances into concrete classes, it will be a nightmare.

What if we put the condiments inside the abstract class Beverage?

There are a few limitations in this design.

- Price changes for condiments will force us to alter existing code.

- New condiments will force us to add new methods and alter the cost method in the superclass

- We may have new beverages. For some of these beverages (iced tea?), the condiments may not be appropriate, yet the Tea subclass will still inherit methods like hasWhip().

- What if a customer wants a double mocha?

To address these limitations, we can apply the Decorator Design Pattern

The Decorator Pattern

The decorator pattern is closely related to the open-closed principle.

Design Principle 5 Classes should be open for extension, but closed for modification

Our goal is to allow classes to be easily extended to incorporate new behavior without modifying existing code.

This makes the system resilient to change and flexible.

Definition / Visualization

Let’s first define the Observer Pattern before we apply that to our design.

The Decorator Pattern attaches additional responsibilities to an object dynamically. Decorators provide a flexible alternative to subclassing for extending functionality

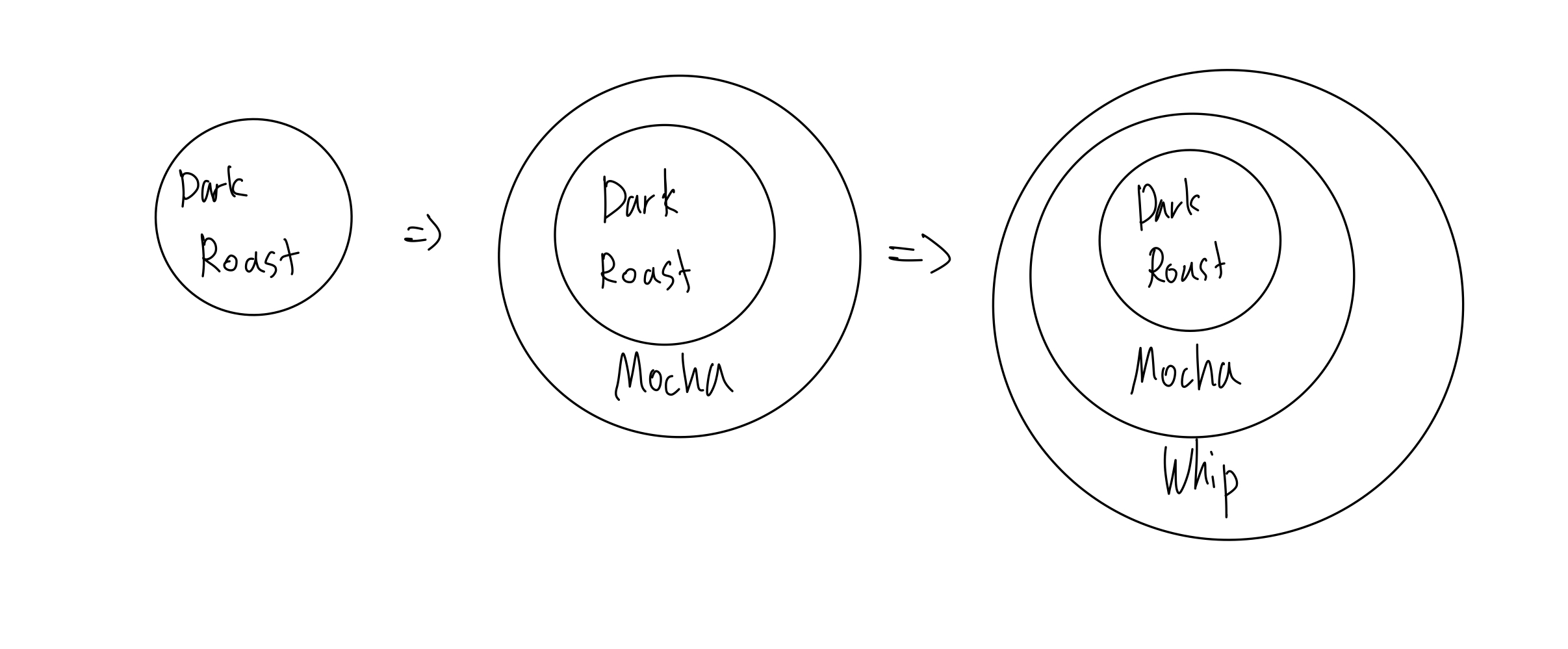

The figure below shows the visualization of the decorator pattern.

Basically, we are wrapping the object with the decorators.

When we want to get the cost of WhipMochaDarkRoast, we can call cost() for Whip object.

Then, the Whip object will delegate the cost() method to the Mocha and Mocha will delegate the cost() method to Dark Roast.

Then we can get the cost of WhipMochaDarkRoast as the inner objects will return their own costs. For instance, DarkRoast.cost() will return $1, Mocha.cost() will return $1 + $0.5, and Whip.cost() will return $1 + $0.5 + $0.8.

There are a few things to note about this pattern.

- Decorators have the same supertype as the objects they decorate. For instance, Dark Roast, Mocha, and Whip objects should all have the same supertype.

- The decorator adds its own behavior before and/or after delegating to the object it decorates to do the rest of the job.

Revisiting the Beverage Class

Now we will revise the Beverage Class using the decorator pattern.

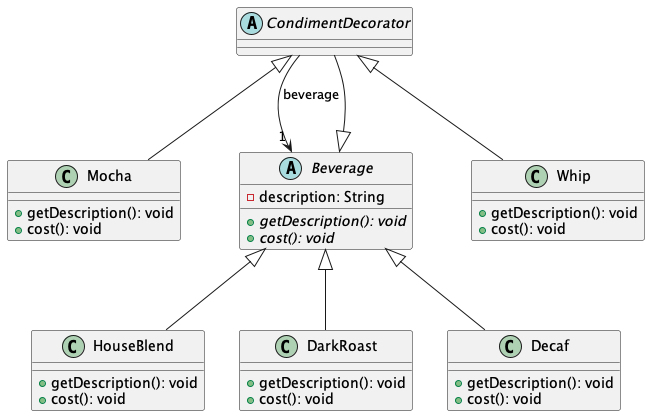

Let’s look at the class diagram.

We can see that the decorators are inheriting from the abstract class CondimentDecorator.

The abstract class CondimentDecorator has Beverage as a component so that the decorators can wrap any Beverages.

In this design, the point is that we’re using inheritance to achieve the type matching, but we aren’t using inheritance to get behavior.

Let’s look at the code now.

public abstract class Beverage {

String description = "Unknown Beverage";

public String getDescription() {

return description;

}

public abstract double cost();

}

public abstract class CondimentDecorator extends Beverage {

Beverage beverage;

public abstract String getDescription();

}

The CondimentDecorator class extends the Beverage class so that Beverage and CondimentDecorator can be used inter interchangeably.

Now we will look at the concrete beverages and condiments.

// Beverages

public class HouseBlend extends Beverage {

public HouseBlend() {

description = "House Blend Coffee";

}

public double cost() {

return .89;

}

}

public class DarkRoast extends Beverage {

public DarkRoast() {

description = "Dark Roast Coffee";

}

public double cost() {

return .9;

}

}

public class Decaf extends Beverage {

public Decaf() {

description = "House Blend Coffee";

}

public double cost() {

return .99;

}

}

// Condiments

public class Mocha extends CondimentDecorator {

public Mocha(Beverage beverage) {

this.beverage = beverage;

}

public String getDescription() {

return beverage.getDescription() + ", Mocha";

}

public double cost() {

return beverage.cost() + .20;

}

}

public class Whip extends CondimentDecorator {

public Whip(Beverage beverage) {

this.beverage = beverage;

}

public String getDescription() {

return beverage.getDescription() + ", Whip";

}

public double cost() {

return beverage.cost() + .10;

}

}

In the concrete condiment classes, we are delegating the cost() call to the object we are decorating.

Here’s some test code to make orders:

public class StarbuzzCoffee {

public static void main(String args[]) {

// beverage without any condiments

Beverage beverage = new Espresso();

System.out.println(beverage.getDescription()

+ " $" + beverage.cost());

// beverage with condiments

Beverage beverage2 = new DarkRoast();

beverage2 = new Mocha(beverage2);

beverage2 = new Mocha(beverage2);

beverage2 = new Whip(beverage2);

System.out.println(beverage2.getDescription()

+ " $" + beverage2.cost());

}

}

We have applied the Decorator Pattern to our app.

Reference

“Head First Design Patterns” by Elisabeth Freeman and Eric Freeman